Learning is a process. The teacher is a life-long learner who designs and guides students through a variety of processes via different experiences. The role of the student is to then reflect and attach personal meaning to these experiences. The process of learning to teach often begins with the experience of attempting and implementing different techniques, strategies, and methods that eventually meld with the individuality of the teacher. I have been fortunate to learn several techniques through my experience in music education and French Immersion teaching in tandem with my journey towards self-actualization.

This post begins with an introduction to one of my main teaching influences, Kodály, and how I have made meaning from my time studying Kodály-inspired pedagogy. I then connect that pedagogical lens to teaching general French Immersion education in British Columbia as well as how I plan to use the same processes I do with my students in my own life-long learning.

The Kodály Influence

I have brought up the name Kodály frequently in my blog. Zoltan Kodály (pronounced KO-dye or /kɔːˈdaːj/) was an influential Hungarian music educator in the early 20th century whose ideas and ideals continue to be a global influence on music education today. His career as a nationally recognized composer and professor shifted towards music education. His life’s work was seeking a means towards Hungarian cultural preservation and revitalization after years of Austro-German influence. He said:

If we build up our school system in this spirit [the spirit of teaching ‘good music’ to students as young as kindergarten] and if we make a little more time for music in the curriculum, it will not be without results. We have to establish already in school children that the belief that music belongs to everyone and is, with a little effort, available to everyone” (Kodály ed. Bónis, 1964, p. 37)

To contextualize a bit further, during Kodály’s lifetime music education was reserved solely for the upper class and folk music was looked upon as ‘bad’ compared to the ‘good’ Western art music. What Kodály did was spearhead a music education movement in Hungary with the vision to bring quality music education to everyone via the school system. He called on his graduate students to seek out the best possible tools throughout Europe to teach music to children. Through decades of collecting and diligent experimentation, the Hungarian music education system of the mid 20th century became an idolized model that people from across the globe flocked to Hungary to learn and take back to their home countries.

Today we continue to grapple with the idea of quantifying different musics as either ‘good’ as well as how to teach music in a culturally appropriate and responsible way; but the overarching ideals that Kodály had continue to influence me to this day: that music should belong and be accessible to everyone. His contemporaries like Klára Kokas (1999) extended his ideal to include people of all abilities and was an early model for inclusion in music education.

The foundation of what came to be known as the Kodály method or approach is singing. Kodály spoke prolifically about the power and need for singing. Through singing, students would learn folk songs of their culture through which they reflected and derived musical elements leading them towards the ability to read, write, and think Western music notation with increasing independence and mastery. This is what Kodály considered music literacy. Music literacy was achieved with carefully crafted lessons that included the use of tools like tonic sol-fa (movable ‘do’ solfège) accompanied by Glover-Curwin hand signs (sometimes now referred to, erroneously, as Kodály hand signs), and Chevé rhythm syllables to concretely experience melody and rhythm. Perhaps the most important of those is the carefully crafted lessons. What has come to be known as “the sequence” is the foundation of a Kodály-inspired teacher’s practice. It is the process of guiding students through the concrete experience of singing to the abstract experience of reading Western music notation.

The sequence has been described in different words. Lois Choksy (1999) outlines it as prepare – make conscious – reinforce, while others use prepare-present-practice as an alternative. What I like about “make conscious” is the idea that it is a moment in the teaching process that teachers simply label what students already have experienced and have fully internalized. For many, this may be semantics but the essence of this sequence has permeated through my whole career and teaching practice.

A purist Kodály-inspired teacher goes through a set of activities that prepare students for a new concept, isolating the musical element and making it concrete visually, aurally, and kinesthetically. Only once the teacher witnesses significant readiness of the students, ensuring the majority have internalized the new concept in all modalities, do they then move to the moment of “making conscious” or “presenting” the name that musicians use for that musical element. This comes but as a brief review of known experiences towards the unknown name or label. From there, the concept is now referred to as “what musicians call” the concept which is then reinforced with known and new carefully selected materials that only include the target concept in relation to the learning. The final stage is to ensure that students can fully read and write the concept independently which they can then either use in their own compositions or improvisations and recognize and apply the concept in all new contexts including the use of instruments.

One of the main strategies from my Kodály education that I continue to use daily is targeted, comparative questions after we learn repertoire with the target musical concept. In the prepare stage of any musical concept we ask students such questions as

- Is it the same or different?

- Is it higher or lower?

- Is it faster or slower?

- Is it longer or shorter?

- Is it louder or softer?

- Is it stronger or weaker?

By zeroing in on what we, the teachers, are hoping students learn, students can start to pay attention to what the target learning is and with repeated experiences this comparative reflection empowers students to find patterns and it builds their capacity to connect with the subject (in this case the song) with increasing independence. Comparative questions scaffold students towards the critical thinking needed to analyze and show readiness for the make conscious or present stage.

The sequence in its purest form takes a lot of time and careful crafting to intertwine the different musical elements for long term design towards the full ability to read, write, and think Western music notation. This ideal of a learning sequence may never be fully possible to implement, at least for myself (not for lack of trying!), but as with any technique, it is not what makes a good teacher.

Technique and the Real Teacher

I can attest to Palmer’s statement that “Technique is what teachers use until the real teacher arrives” (The Courage to Teach, 1998, p.5). My early career was spent trying to master the Kodály method trying to be a great teacher. I would often get frustrated with myself, my students, and my colleagues for not understanding my passion for wanting to realize the ideal education I learned in my Kodály certification courses. Now with experience I feel like I am moving towards the “real teacher”.

Parker explains,

Good teaching cannot be reduced to technique; good teaching comes from the identity and integrity of the teacher… my ability to connect with my students, and to connect them with the subject depends less on the methods I use than on the degree to which I know and trust my selfhood – and am willing to make it available and vulnerable in the service of learning (p. 10).

I used the Kodály “technique” without even considering my selfhood for several years of my career before I truly awakened to a more present life. This being said, I can attest that my deep learning and experimentation with Kodály-inspired “technique” was a necessary part of the actualization towards my “real teacher” self. It was through my experiences that I realized that I am a dedicated, diligent, disciplined, and thoughtful educator who feels secure when there is an intentional plan. These are gifts I can offer my students: inspiration, intention, and integrity. What Kodály has done for me is provide me a solid foundation of intentionality: critical pedagogical thinking, curriculum design, and implementation. When my integrity and my technique combine I can offer students a well-designed experience from which they can derive their own personal meaning.

From Music to French

The Kodály lens extends to my experience teaching French Immersion. The parallels between music education and supplementary language acquisition and literacy, including teaching aspects of the musical culture, have been staggering and exciting. In my first year of teaching French Immersion I was given Lyster’s book Vers une approche intégrée en immersion (2016) [Towards an Integrated Approach in Immersion] and saw immediate, almost uncanny, connections between his proactive integrated approach to my well-known Kodály sequence. Lyster outlines his proactive teaching sequence as “perception, conscientisation, pratique guidée, pratique autonome [perception, make conscious, guided practice, autonomous practice]” (p.53). Could this be but a linguistic translation of prepare, make conscious, reinforce, practice? I searched his works cited and no reference to Kodály or music education was listed. How could there be such a stark similarity?

What both Kodály and Lyster offer is a pedagogical process and framework that I can use to help design my teaching experiences for students and in many ways. I have contextualized both through the lenses of backwards design and guided inquiry and Universal Design for Learning, all of which are foundations of the BC Curriculum. In the early days of curriculum implementation, my partner, Mr. Tong, helped me realize that the whole curriculum is based on Curricular Competencies which are framed as learning processes for several subjects including Science, Social Studies, Applied Design, and the Arts. In my early career, I spent time aligning my understanding of Kodály and the BC Arts Curriculum and sought a way to make the creative process conscious to my students. The simplified version I derived was Create-Refine-Share.

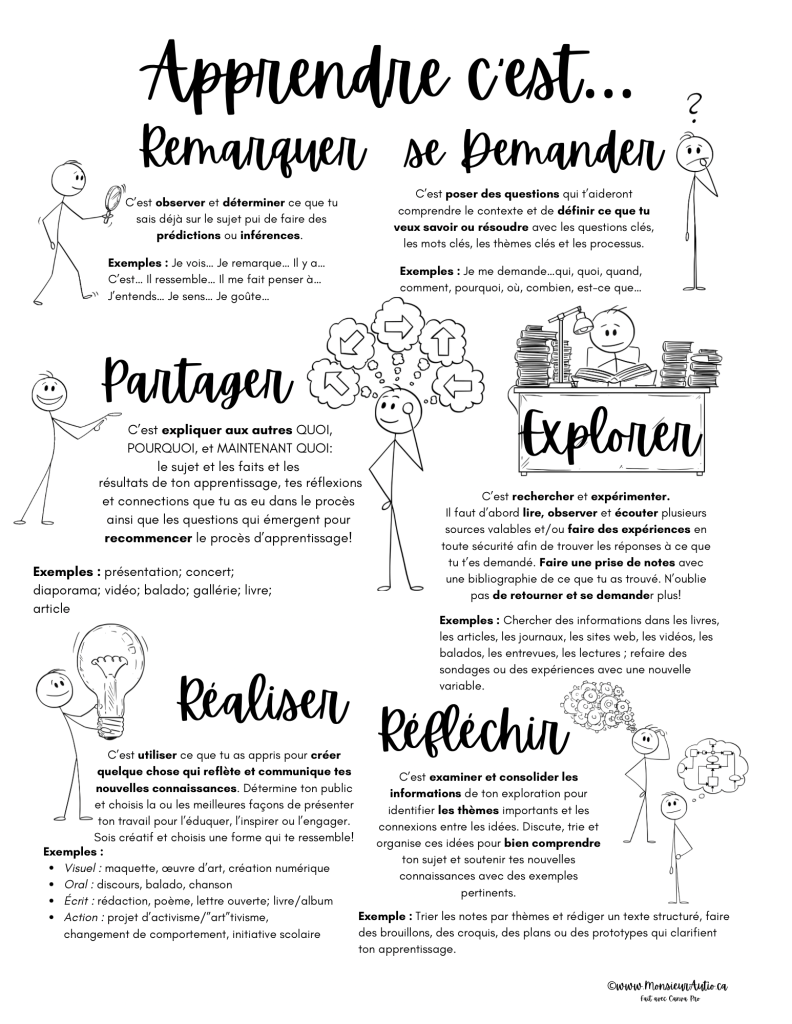

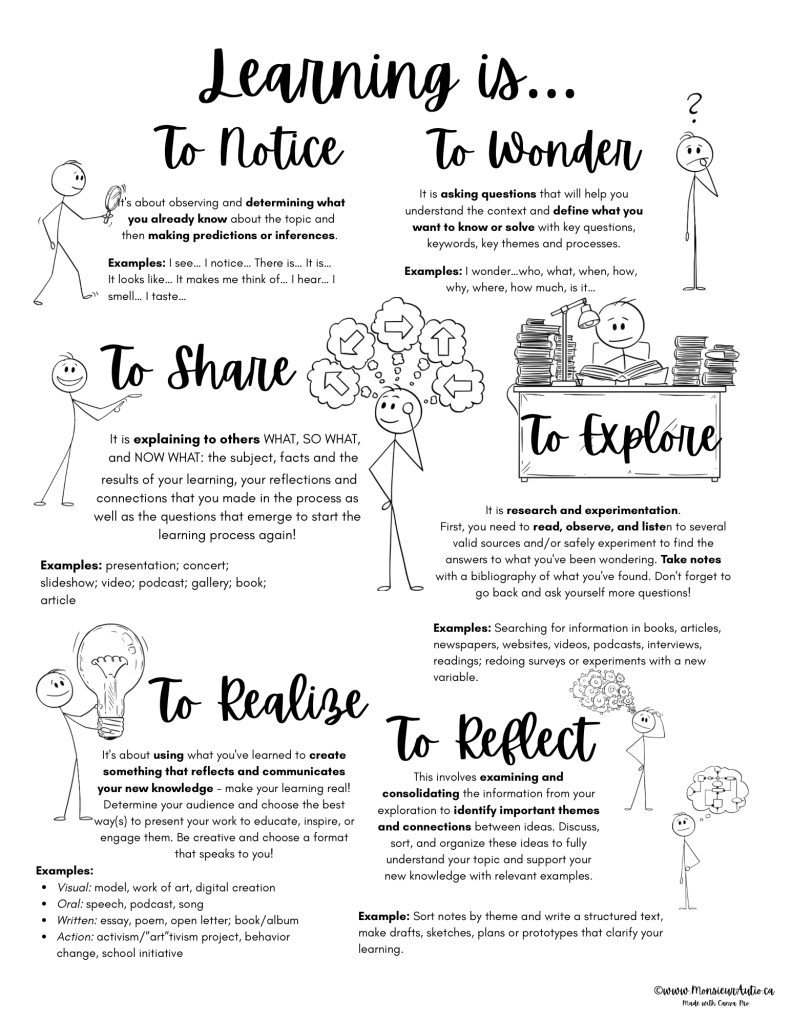

I was further inspired by Mr. Tong when he taught an inquiry course at his secondary school that combined Grade 8 humanities and sciences. He had the idea to create one overarching process to help guide students and show them the interconnectedness of learning. This year I wanted to find a streamlined process that combined Arts Education creative process, Applied Design process, the Scientific Method, the Social Sudies inquiry process from the BC Curriculum in addition to various inquiry processes (for instance from the THINQ series), as well as Kodály and Lyster’s sequences. With the help of AI I was able to synthesize them to a process that has worked effectively in all subject areas: remarquer, se demander, explorer, réfléchir, réaliser, partager [notice, wonder, explore, reflect, make, share].

I have created a large display in my classroom (thanks Canva!) and refer to it often as we are learning. In the middle is a bidirectional circle of arrows to show that the learning is not always linear and that, as with any circle, has no true beginning or end. Moreover, it has become the framework for my project planning. The visual helps us as a learning community know where we are, where we’re going, and where we came from. When it comes to reflecting on our experiences, it gives us common language and simplifies how we learn. Perhaps this even acts as a version of the “preparation” phase for my intermediate students who will later make each process conscious as they progress in each learning area.

I have created a version that goes into each of our inquiry booklets (French and English Available) with expanded information about each stage.

As a life-long learner I am embarking on a new adventure myself. I have started my first course towards a Teacher Librarian Certificate and I will be using our class’ process to do my own inquiry! Some of my next posts will be course requirements but also true inquiry for my own practice. I plan to spend time noticing and preparing my inquiry by asking lots of questions and wondering before diving deep into the research and exploration of my topic, reflecting on it through this blog and making some sort of product I can share with you all at the end! Then, the cycle begins again!

Where do you see yourself in my story? Share in the comments!

What pedagogical structure/technique/method/sequence have been foundational for your practice? What verbs would be in your sequence?

Why do you think there is such a close parallel between Kodály and Lyster’s sequences?

Was there a specific tip from this blog post that you feel you will implement?

Autios! À la prochaine!

Bibliography

British Columbia Ministry of Education and Child Care. (n.d.). B.C. curriculum. https://curriculum.gov.bc.ca/

Choksy, L. (1999). The Kodály method I: Comprehensive music education. Ed 3. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River NJ.

Kodály, Z. (1964). The selected writings of Zoltán Kodály. Ed. Fervency Bónis, translated by Lily Halápy & Fred Macnicol. Boosey & Hawkes, London.

Kokas, K. (1999). Joy through the magic of music. Translated by Ágnes Péter & Jerry-Louis Jaccard. Edited by Jerry-Louis Jaccard. Akkord. Budapest, Hungary.

Lyster, R. (2016). Vers une approche intégrée en immersion. Éditions CEC, Anjou, QC.

OpenAI. (2025). [Monsieur Autio Teaches ‘mi’] [AI-generated image]. ChatGPT. https://chat.openai.com/

Palmer, P. (1998). The Courage to Teach: Exploring the Inner Landscape of a Teacher’s Life. Jossey-Bass. San Francisco, CA.

Watt, J. & Colyer, J. (n.d.) THINQ series. Waver Learning Solutions. Toronto, ON.

Leave a reply to Monsieur Autio Cancel reply